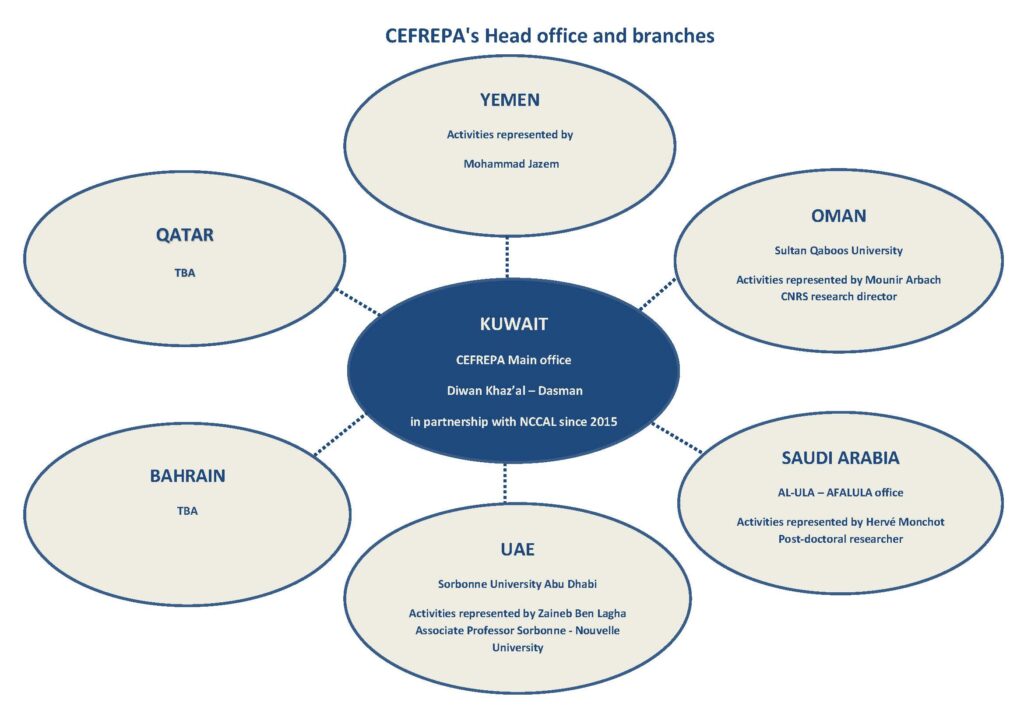

Headquarters and Antennas

Since 2015, the French Research Center of the Arabian Peninsula (CEFREPA) has been housed near the Arabo-Persian Gulf in a 1950s house renovated and made available by the Kuwaiti State, a stone’s throw from the famous Kuwait Towers and facing the British Embassy. The residence is part of a heterogeneous architectural ensemble, the major piece of which is a Diwan built at the beginning of the 20th century and today uninhabitable because it is in an advanced state of deterioration (opposite, the headquarters of the CEFREPA, the ruins of the Diwan and the al-Hamra tower, photograph M. Ayachi). The land, in constant transformation, is a patchwork of styles and eras. A maze of dusty walls, 1950s tiles, charred window jambs, obsolete electrical installations and abandoned kitchen utensils, surrounded by a few more recent villas, partly restored and partly in ruins, the Diwan Khaz’al questions because it is not open to visitors and nothing on the site informs about its past. It seems to have lived several existences and superimposes successive layers of occupation, but all ephemeral, which draw up a summary of Kuwaiti architectural history. Fewer years passed between the construction of the Diwan (circa 1916) and that of the three surrounding villas (1950s) than between the construction of the latter and the erection of the 412-metre tower al-Hamrah (2011). The buildings, in the first place the Diwan Khaz’al, are therefore witnesses in their splendor and their deterioration of the rapid modernization of the country, and of the history of Kuwait over the past century.

At the origin of the Diwan is the friendship between two Arab sheikhs at the turn of the 19th century and the 20th century. Many personal and geopolitical reasons prompted Sheikh Mubarak al-Sabah (r.1896-1915) and Sheikh Khaz’al al-Ka’b (r.1897-1936) to come together. Both are chiefs of an Arab tribe; the first is the strong man of the Utubs, a tribe of Naj settled in Kuwait since the 17th century; the second leads the Banu Ka’b, an Arab tribe of Western Persia, and bears the title of Sheikh of Muhammarah (today Khorranshahr). Both are ambitious leaders who came to power at the same time after the assassination of their respective brothers. If they are neighbors, on both sides of the Shatt el-Arab, they are however not competitors, because their two territories are located on the outskirts of two different empires, the Ottoman Empire for one and the Empire qajar for the other. They also benefit from a position at the crossroads between four competing empires, Ottoman, Persian, British (in the Gulf), and to a lesser extent Russian. Both finally, in the context of the weakening of the Eastern empires and the rise of the British in the Gulf, embarked on the path of autonomy. Mubarak, often considered the founder of modern Kuwait (from him descend the two branches of al-Sabah which still rule the country today) was appointed in 1897 qaim maqam (deputy governor) of Kuwait by the Ottoman sultan, thanks to the intervention of the British; sixteen years later, Great Britain obtained from the Young Turks that Kuwait be recognized as a province in its own right, autonomous from that of Basrah. On the Iranian side, the British ally protects the rights of Sheikh Khaz’al with Tehran, which allows him to extend his principality in Persia, Abadan or Bahmansir, but also his influence on the other side of the Shatt el-Arab through an active land purchase policy. The economic benefits of the discovery of oil near Abadan, and the shares of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company offered by the British, contribute to its enrichment.

The similarities with the Malek Palace in Bushehr on the Iranian Gulf Coast (the rectangular and massive plan, the corner turrets, even the materials used) suggest that the Sheikh was inspired by it, even that he brought the same architect to Kuwait. If the construction techniques, the use of coral stone, a local material, of earth as mortar and for coatings, and of mangrove beams, recall the traditional Kuwaiti habitat of the old city (including the Bayt al-Badr is today one of the last testimonies), the architecture of the Diwan is for the rest unique in Kuwait. First of all, by its size, because two-storey buildings were rare in the region at the beginning of the 20th century, even palaces. Then by its form, since the four turrets, connected by open verandas, assimilate the structure to a fort, which the building has never been. The exterior, despite carved wooden pillars and ornate windows, remains sober compared to the palace on which the Diwan depends. The interior decoration can only be understood from photographs from the 1960s (see below), which show the similarity between the rich wooden ceilings and those of the palace. The layout of the rooms on the two floors, not to mention a deep cellar between the two eastern towers, recalls the function of the place: on the first as on the second, a corridor crosses the Diwan lengthwise, from one door to the on the other, and serves on each side three square rooms of equal size, intended to accommodate the guests. The whole mixes Arab, Persian and Indian influences, but its earthen architecture explains its fragility and its continuous deterioration since the 1960s, when the mastery of traditional know-how was lost.

The Sheikh Khaz’al did not benefit from the Qasr and the Diwan for long, since his power suddenly collapsed in the 1920s, unlike that of the Kuwaiti sheikhs who, much less rich than him, continued to be supported by the British. Sheikh Khaz’al must face the rise of Tehran and the consolidation of the Persian Empire under the aegis of General Reza Khan after his coup in 1921. The latter, even before his enthronement as Shah in 1925 and the change of dynasty, begins a process of unification which passes by the setting in step of the regional principalities. The Sheikh Khaz’al is in this respect a privileged target, commensurate with the danger he represents for the new power whose ideal is a single nation in a modernized State: the Sheikh claims Arab identity in the face of the assertion of Iranian identity, represents tribal power against the central state, and is finally at the head of a rich oil region. The Sheikh Khaz’al tries to resist by allying himself with the Bakhtiary tribes that he still faced a few years earlier, but their military forces are easily defeated at the end of a short war (1922-1924), considered as a rebellion by Reza Khan. After an act of forced contrition, the Iranian lands of the Sheikh are taken over by the new Shah who has his former rival removed. He was under house arrest in Tehran until his death, probably assassination, in 1936.

The Sheikh Khaz’al’s family probably continued to occupy the Qasr and the Diwan during his captivity, but were forced to sell them when he died. The palace was sold to the al-Ghanam family, whose name it bears today, and who occupied it until the 1970s. The Diwan did not remain unoccupied either, since it was bought by Abdullah al-Jaber al-Sabah which gives it its current name. In the 1930s, the man was president of the Council of Education (the ancestor of the Ministry of Education). Grandson of Sheikh Abdullah bin Sabah al-Sabah (r.1866-1893), he does not descend from Mubarak and is therefore part of a branch removed from the succession, but not from circles of power. As for the Khaz’al al Ka’b family, it is falling apart; if the eldest sons and their family won Europe thanks to the fortune of their father, the youngest son, his daughters and their descendants, unable to reach Iran, remained in Kuwait where they now live in anonymity.

Since 2008 and the acquisition of the land by the National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters (NCCAL), the palace, classified Heritage by the State, the Diwan, and the houses which surround it have reinforced their heritage function, which inscribes them in the continuity of the national museum. The Diwan, under the name of “Sheikh Abdullah al-Jabir Palace” is one of the four places deposited from 2014 by Kuwait on the UNESCO World Heritage List (along with the towers of Kuwait, close to the Diwan , the island of Boubyan and the remains of the island of Faïlaka).

The Diwan is no longer accessible to the public. An attempt at restoration, following short archaeological excavations, was unsuccessful and the rapid alteration of the earthen building continued. Since the archaeological surveys took place, what remained of the north facade, a main staircase and part of a turret have collapsed. The only restoration completed on the site, that of two of the three houses built for the eldest sons of Abdullah al-Jaber al-Sabah, which have been returned to their appearance in the 1950s. totally in ruins. Since 2015, the French Center for Archeology and Social Sciences has occupied the second of these residences and perpetuates the heritage function of the place.

The Diwan ruins in 2017 (photograph H. David-Cuny)