The Face Mask : a desperate measure

- admcef22

- January 30, 2023

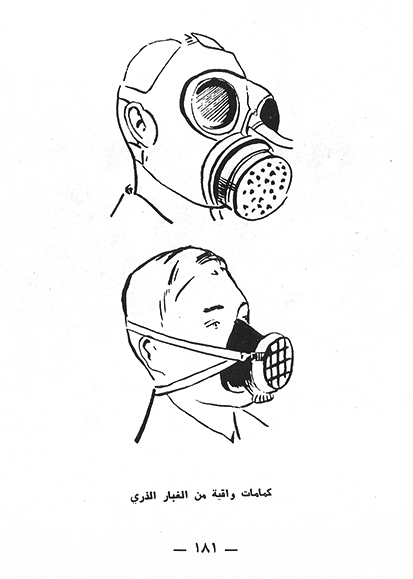

As an iconic, distinctive and evocative object, the gas mask is an instantly recognizable form of the material and visual culture of war. Its invention was developed to protect individuals from toxins and poisonous substances in the air, covering the mouth and nose from airborne hazards. It is a peculiar respiratory object that has withstood categorization, used in military, industry, the service sector and policing (Fig. 1). Collected, curated and studied, gas masks operate as clothing, art objects, costumes, medical aids, and protective equipment. As a mask, it can be regarded as a means of disguising, transforming or displaying identity, but also carries with it an association of threat and danger. It is an ominous symbol, perhaps even suggesting paranoia, and the performance of wearing it implies a menace from without to which the wearer is reacting.

Just as a mask can disguise or transform identity, a gas mask conceals and alters the senses and is the sensorium’s shield against chemical warfare attacks. During the 1990 Gulf War, the Kuwaiti population were faced with the threat of chemical warfare by Iraq, such as mustard and nerve gas. The exposure of these gases on an unprotected civilian population in dense urban areas can result in a large-scale disaster. In a desperate response, the Kuwaiti Underground Resistance (Al- moqawama) distributed formulas for DIY gas masks through leaflets and word of mouth. The instructions were unsophisticated, utilizing available materials such as charcoal, cloth and thread. Kuwaiti men, women and children created workshops in their houses where they stitched garment masks filled with crushed charcoal and activated in water.

In the video performance ’Semiotics of War in the Kitchen’ (Fig. 2), I attempt to recreate a gas mask in my grandmother’s kitchen, where my mother and aunts created one for each member of our family during the war. The result was messy, primitive and futile, a realization they had made after stitching over a dozen masks. Nonetheless, the masks’ aesthetic qualities demonstrated the potential richness of the relationship between people and things ; between my family and their homemade respirators in wartime. Defeated and disheartened, and as a final form of defiance, they put their faith and trust in God.

In 1998, another opportunity for Iraq to attack using biological and chemical weapons made the gas mask a precious commodity. Citizens rushed to buy the first stock of protective suits and masks, fearing that the nation could again fall victim to the Iraqi forces. The marginalized and immigrant community residing in Kuwait borrowed the inadequate processes of the DIY gas masks used by citizens eight years ago : “We are preparing for the precautions against Saddam’s chemical and biological gases. We can’t afford the gas masks. We sprinkle crushed charcoal on a damp handkerchief and wrap it around our nose,” explained an Indian migrant worker in an interview with The Associated Press (AP, 1998).

– Corona Principles vs Norms

In light of the sudden global COVID-19 pandemic, people tasked themselves or were tasked, in an innovative response to this biting global issue. A worldwide shortage of face masks has given rise to a new trend of homemade alternatives, as people look for ways to quell boredom and help out amid the pandemic. The virus’s avatar presents itself in a variety of designs, hiding its user’s face but also communicating in today’s ’fashionable’ dystopia, further perpetuating class difference and divide. They are becoming a symbol of this era, a shield against the micro, unseen viral enemy, as a commodity and political statement. The unease around inconclusive science and shifting government guidance has muddied the political debate, making the mask a visual shorthand for a current culture of individualism, nationalism and consumerism.

Fear and anxiety are symptoms of extreme events, particularly new threats, and the face mask currently plays a significant role in the stigmatization of people. A Chinese student was verbally and physically harassed in the UK, and a Chinese woman was assaulted in New York, both for wearing a mask. A security guard was shot in Michigan for refusing a mask-less mother and her child from entering the store, and in Saudi Arabia, an image of an Asian migrant worker, dressed as a human hand sanitizer while wearing a face mask for Saudi Aramco, went viral.

The face mask : its presence, principles and history force us to look beyond its simplistic models as social mediator and protector, and towards a more nuanced understanding of the mask as an animate agent acting upon people and acted upon in turn. From chemical warfare to coronavirus anxiety, protective face masks have become and may well remain a global social norm, forced upon us by rapidly shifting social circumstances. Explicit moral arguments for and against them may lead people into a false sense of protection and not wearing them may increase the risk of transmission. In turn, many of us look towards the future impassively, and our face masks with apprehension while placing our faith and trust in God (Fig. 3).

Voir en ligne : Read more about the author..